What is Turner Syndrome?

Turner syndrome (TS) is a genetic condition occurring predominantly in girls and women. It is caused by the absence of all or part of the second sex chromosome. Female babies born without TS typically have 44 numbered chromosomes plus two X chromosomes (46, XX). In typical TS, there are the same 44 numbered chromosomes, plus one X chromosome and one missing, which is marked as an O (45, XO). When cells within the same person with TS have a mixture of multiple sex chromosome arrangements it is called “mosaicism” or “mosaic” TS. There are other types of X chromosome structures that can cause TS that all have a missing section of the X chromosome as the common feature. These include: chromosome deletions, isochromes, and ringed chromosomes.

The only absolutely necessary feature for a diagnosis of TS is the missing portion of the second sex chromosome. There are a variety of physical characteristics and associated conditions which occur in TS that are described below. There are some people who have very few of these conditions, and others who have many or severe findings. These conditions include a number of serious health problems that commonly occur in the general (non-TS) population but occur in TS with significantly higher frequency.

How common is Turner syndrome?

TS occurs in approximately one out of every 2,000 – 4,000 female live births.

What causes Turner Syndrome?

While TS is a genetic condition because it involves an abnormality of a chromosome, it is typically not an inherited condition or one that runs in families. TS occurs by chance early in pregnancy and is due to the loss of a sex chromosome. This loss leaves the baby with only a single X chromosome or an X chromosome and only part of a second X chromosome (there are usually two) in each of their cells. The age of a parent, their ethnicity, diet, or other factors do not lead to TS. Importantly, there is nothing that either parent can do before or at the start of pregnancy that will prevent or decrease the risk of having a child with TS.

What are the features of Turner syndrome?

TS affects many body systems and organs, and the features can present at various times throughout life. The most common features of TS include short stature (Figure 1), short thick neck, certain facial features (Figure 2), heart defects, hormonal abnormalities, delayed puberty, and infertility (decreased chance or inability to become pregnant). Some babies with TS are born with swelling of the feet or neck, called lymphedema. Other issues include abnormally shaped kidney (“horseshoe kidney”), hearing loss, and thyroid abnormalities. Certain learning disabilities are more common in girls and women with TS. These include nonverbal communication skills and executive functioning issues.

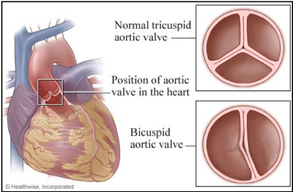

Heart defects are one of the most common features of TS, and for many families may be one of the most concerning. Somewhere between 25-50% of patients with TS are found to have some type of abnormality relating to the heart and blood vessels. The most common defects affect the left side of the heart, which is the part responsible for pumping blood to the body. These include a bicuspid aortic valve, coarctation of the aorta, and elongation of the thoracic aorta. A bicuspid aortic valve (Figure 3) is a common abnormality that occurs when the aortic valve has two leaflets instead of the usual three leaflets. This can lead to the valve not functioning properly over time.

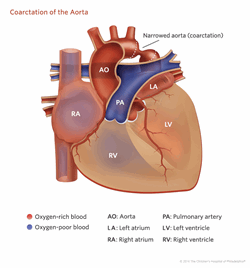

Coarctation of the aorta (Figure 4) is seen when the aorta, which is the main blood vessel that takes blood from the heart to the body, becomes narrowed and forms a blockage at the beginning of the descending aorta. Elongation of the aortic arch is a very mild feature that is seen on pictures of the heart but is of unclear importance. Other cardiac defects that can be seen are abnormalities of the veins returning to the heart from the body or the lungs. More rare defects include hypoplastic left heart syndrome, abnormalities with other valves, and various types of holes in the heart. One of the more common problems in patients with TS is high blood pressure, which requires careful monitoring. In addition, there have been reported problems with electrical conduction in the heart (long QT measurement on the EKG) and heart muscle weakness.

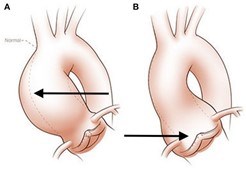

Over time, one of the most important concerns is that the aorta can begin to get larger (dilates). This happens most frequently in the first portion, the ascending aorta (Figure 5). Risk factors for aortic dilation include bicuspid aortic valve or high blood pressure but can be seen in any person with TS. If the aorta continues to get larger, there is increasing risk that the aorta can tear (aortic dissection) (Figure 6), which is a rare but life-threatening complication.

Some babies with TS do not have any of these issues at birth but develop other features of TS later on (slow increase in height, lack of pubertal development, trouble conceiving, development of autoimmune disorders, high cholesterol, high blood pressure, and aortic aneurysm and dissection).

(from 2017 Yassine NM et al. Front Physiol 2017; Copyright: Glen Oomen, M.Sc.(Link)

What kind of testing is needed?

TS is diagnosed by lab testing (blood, saliva, or cheek swab) using a technology that analyzes chromosomes. Most girls/women with TS can be diagnosed by “karyotyping,” a long-time method of counting up chromosomes under the microscope. Additional chromosome testing technologies are sometimes considered based on karyotype results to further determine the specific X chromosome variation or for mosaicism. In about 10% of individuals with TS, some of the body cells contain fragments of Y chromosome, which can increase the risk of developing tumors, called gonadoblastomas.

Girls and women may be first diagnosed at various times in life, including prenatally, in infancy, during childhood, or even in adulthood. The sooner TS is diagnosed, the better chance to try to prevent some of the complications of the condition. Thus, girls or women with features of TS should have a karyotype test performed by their doctor or referred to a geneticist or endocrinologist for testing.

There is some controversy in the field about how to classify individuals who are born with male physical features and have a mosaic karyotype that includes a mixture of normal male (46 XY) and Turner syndrome (45 XO). We prefer to be inclusive of all with a mosaic karyotype and will include those males in the broader definition of Turner syndrome. Furthermore, some of these individuals can have the same cardiac findings as women with classic Turner syndrome. Therefore, based on our current knowledge, boys and men with a mosaic 45XO karyotype should be generally screened similarly to the rest of the population with Turner syndrome.

What happens after a Turner syndrome diagnosis?

When someone is first diagnosed with TS, a number of screening tests are recommended to check for medical issues that can happen in individuals with TS. It is important to have these tests even if an individual is not having any unusual symptoms, as some medical conditions may be present and can be diagnosed before symptoms arise. Early diagnosis of underlying medical problems may lead to earlier treatment and less severe problems.

Screening tests after a diagnosis of TS include the following (see Appendix 1 for a summary chart that can be printed):

- Ultrasound of the kidneys

- Echocardiogram (ultrasound of the heart) and electrocardiogram (also known as ECG or EKG, which checks for an abnormal heartbeat or arrhythmia)

- Hearing test

- Lab tests for thyroid function

- Eye exam (ophthalmologist)

- Dental exam (if not before diagnosis)

- Skin exam

- Hip X-rays (for newborns with TS)

- Neuropsychological testing if concerns are present, such as learning delays, executive functioning challenges, and/or other behavior or mood disorders

Many girls and women with TS are followed by a number of specialists in addition to a primary care provider. Examples of specialists who care for girls and women with TS are endocrinologists (treat growth issues, hormone imbalances), ENT/audiology (ear/hearing loss), cardiologists (heart, aorta), and fertility specialists.

While the genetics of TS is different than other HTADs, girls and women with TS are at risk for aortic aneurysm and dissection and need to be monitored and treated for aortic complications.

How is Turner syndrome treated?

There is no specific treatment for TS. However, there are treatments aimed at each of the features associated with TS. For example, girls with poor growth may be treated with growth hormone. In addition, there may be treatment with medications by an endocrinologist if there are problems with the thyroid or pubertal development. Some people require treatment with estrogen or progesterone as they grow and develop.

From a cardiac standpoint, treatment is aimed at the underlying problem. For example, conditions such as coarctation of the aorta and hypoplastic left heart syndrome may require early surgical repair. Some people with a bicuspid aortic valve will need valve replacement later during their lifetime. High blood pressure should be treated with medication, usually a beta-blocker or angiotensin receptor blocker. Most importantly, people with TS require careful follow-up throughout childhood and adulthood to monitor any underlying problems and to measure aortic size as they age. In childhood, follow up is generally every six months to two years for people with heart defects or with early signs of dilation of the aorta. Children with completely normal cardiac findings should have screening every 3-5 years. In adults, screening is generally every 6-12 months for the highest risk group, and every 1-5 years for those with some underlying cardiac change or aortic dilation. For adults with completely normal cardiac testing, screening by a cardiologist should remain every 5-10 years. For all groups, screening may include an echocardiogram (ultrasound of the heart) or Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI). In children, an echocardiogram is usually recommended and an MRI completed when they are able to lay still without sedation.

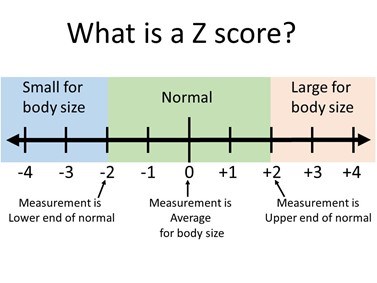

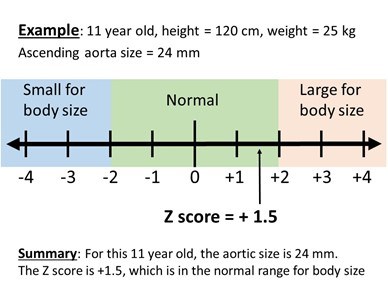

For people with TS who develop severe enlargement of the aorta, there are a wide range of surgeries available, depending on the status of the aortic valve, location of the dilation, and patient age. In some cases, the aortic valve can be repaired, while in others it can be replaced with different types of materials. When evaluating aortic enlargement (dilation) in TS, it is important to relate the aortic size to the girl/woman’s body size. For girls under age 15 years old, this is measured by a TS specific Z score calculator (Figure 7 and 8). To do this, the actual measurement of the aorta (in mm), and the current height (in cm), and weight (in kg) are put into a special online calculator to find the “Z score” for the measurement. A Z score of zero means that the aortic measurement is the average size for a girl with TS with that height and weight. A Z score below -2 means the measurement is small for body size and a score larger than +2 means that the measurement is large for body size. Measurements between -2 and +2 are considered in the normal range. In girls over 15 and adult women, a different method for determining aortic enlargement is used. Because women with TS have short stature, an aortic size that is only mildly dilated as compared to a normal sized adult woman may be significantly dilated for the woman with TS. For example, if an adult with TS has an aortic diameter of 4.2 cm and a body surface area of 1.6 m2, her aortic size index (ASI) would be 2.6 cm/m2 (which is 4.2 cm divided by 1.6 m2). In TS women, the cardiologist may recommend preventative aortic surgery for an ASI of >2.5 cm/m2.

Are there limitations on exercise?

While there are no formal guidelines for physical activity in people with TS who have a normal sized aorta, the level of activity restriction is based on the underlying heart disease. For individuals with no significant cardiac disease, or with only very mild changes in the aortic valve or aorta, there are no activity restrictions. Given the lifelong risks of high blood pressure and obesity, a daily regimen of exercise is encouraged to live a heart healthy lifestyle. Unlike some of the other conditions that can affect the aorta, there does not appear to be an increased risk associated with bodily collision in patients with a normal sized aorta. For those with moderate to severe changes in aortic valve function or dilation of the aorta, there may be restrictions on intense physical activity, competitive sports, or weightlifting.

How does Turner syndrome affect one’s ability to start a family?

Pregnancy in women with TS may be associated with several important health issues, including high blood pressure, preeclampsia, premature birth, low birth weight, and need for cesarean delivery. Of particular concern is that pregnancy may increase the risk for aortic dissection in TS.

Risk factors for aortic dissection during pregnancy include aortic dilatation (enlargement), bicuspid aortic valve, high blood pressure, and coarctation of the aorta.

Assisted reproductive therapy (ART), which is often necessary in women with TS given the associated fertility issues, may pose additional risks for significant complications beyond natural pregnancy.

All women with TS should discuss pregnancy and ART risks with their doctors before considering pregnancy. The decision on whether or not to proceed is always on an individual basis and should be a shared decision, whenever possible. Some general recommendations are listed below:

- Before pregnancy

- It is recommended that ART and spontaneous conception be avoided in women with TS with an ascending aortic size index (ASI) of >2.5 cm/m2 or (history of) aortic dissection. In women with additional risk factors, this threshold is lowered to 2-2.5 cm/m2.

- Women who have had composite graft surgery (where the aorta has been replaced by a surgical graft including a mechanical aortic valve) need special guidance because of the potential for harmful effects of warfarin on the developing fetus. While it is thought that prior aortic root surgery decreases the risks associated with pregnancy for women with TS, this does not eliminate all risk since other aortic segments can enlarge and tear (dissect).

- Imaging of the thoracic aorta and heart with echocardiography and CT scan or MRI should be performed within 2 years before pregnancy or ART in all women with TS.

- Some blood pressure lowering drugs are harmful for the fetus and should be switched to safer drugs prior to pregnancy.

- Monitoring during pregnancy

- Pregnant women with TS should be followed at specialized centers by doctors who are familiar with TS.

- Women with a normal aortic size (ASI <2.0 cm/m2) or any other risk factor should have a clinical cardiovascular check-up with echocardiography at 20 weeks gestation – in all other women, more regular monitoring (every 4-8 weeks) is required.

- Strict blood pressure control during pregnancy is mandatory in all women with TS.

- Delivery (to be discussed on a case-by-case basis!)

- Women with a normal aortic size (ASI <2.0 cm/m2) can have a vaginal delivery.

- The mode of delivery in women with TS with an ascending ASI of 2.0 – 2.5 cm/m2 should be carefully considered – adequate epidural anesthesia is required in all and, in some cases, cesarean section may be considered.

- Whenever the ASI exceeds 2.5 cm/m2 or if a woman has had a prior aortic dissection, cesarean section is recommended.

What are the signs of an acute aortic event? What should be done if one occurs?

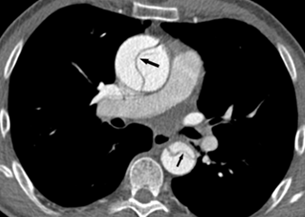

Women with TS are at a much greater risk of aortic dissection (a tear or rupture between layers of the aortic wall) (Figure 6) than the general population. It is a rare, but important complication that occurs in approximately 40 out of every 100,000 people with TS. In general, aortic dissection most commonly presents in men aged 60-80, where women with TS who experience an aortic dissection typically present between ages 25-50. That’s why it’s important to know the signs of an aortic dissection and what to do.

An individual who knows their TS diagnosis has an advantage in the event that they experience unexplained severe or sharp chest, back, or abdominal pain. A person who does not know they have the disorder may not be treated with the same urgency as those who know they are at increased risk of aortic dissection. Since emergency departments may be very busy and knowledge about TS may vary greatly, it is possible that individuals with TS will need to advocate for themselves should they experience these symptoms. They should not be shy about telling the doctors and nurses at the hospital what they know about their condition and the information about aortic dissection and its diagnosis and treatment – which is very different from treatment of myocardial infarction (heart attack), for which aortic dissection is often mistaken.

During an aortic dissection, the pain may be severe, sharp, or tearing, and it may travel from the chest to the back and/or stomach. Some patients with acute aortic dissection have symptoms due to complications of the dissection including shortness of breath, passing out (syncope), stroke or paralysis, or pain in an extremity due to poor blood flow. Sometimes, the pain is less severe, but a person still has a feeling that “something is very wrong.” If a dissection is suspected, a person needs to go to a hospital emergency department right away. The typical evaluation for aortic dissection involves getting a CT scan as soon as possible and is different than the usual work up for chest pain in young women.

Unless someone has a known diagnosis of TS, reports of chest pain often do not automatically raise the possibility of aortic dissection in the emergency room.

Therefore, individuals with TS should be prepared to:

- Advocate for themselves by telling emergency department staff that they have Turner syndrome, are at risk for aortic dissection, and need a CT scan as soon as possible.

- Communicate effectively with doctors and nurses in the emergency department.

Where can I learn more about Marfan syndrome?

Turner Syndrome Society of the United States: https://www.turnersyndrome.org/

Turner Syndrome Foundation: https://turnersyndromefoundation.org/

Turner Syndrome Global Alliance: http://tsgalliance.org

Guidelines:

Cardiovascular Health in Turner Syndrome: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association

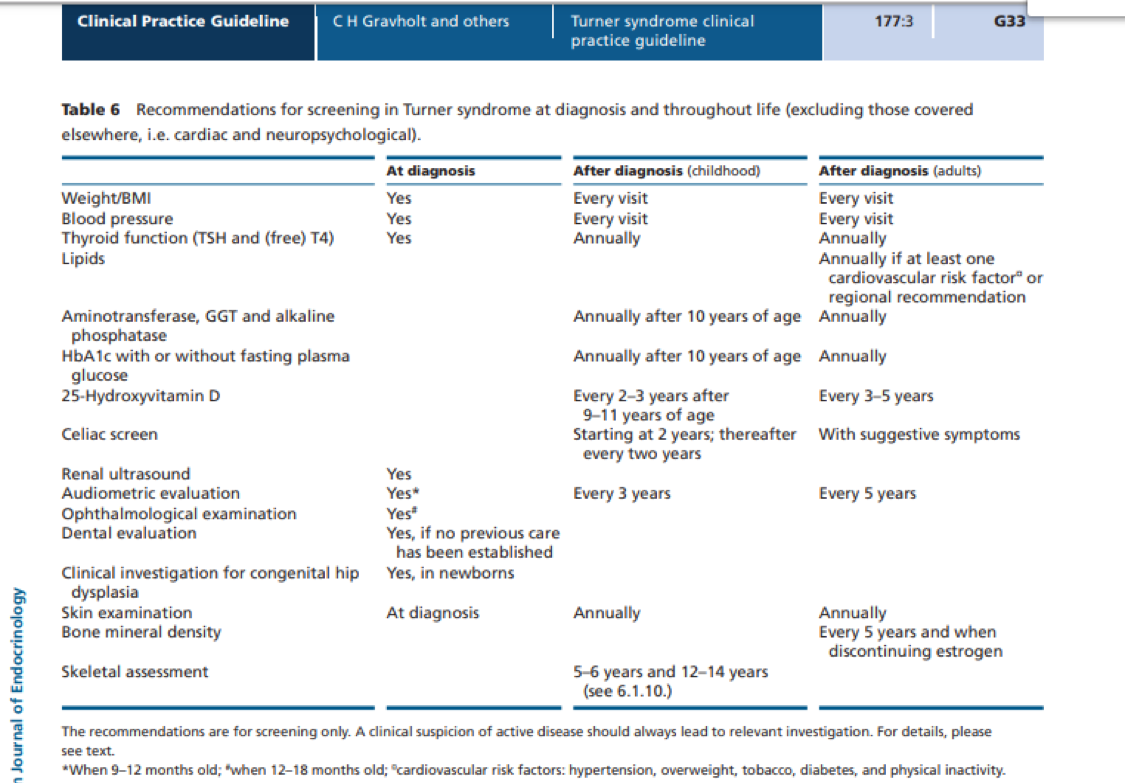

Appendix 1: Recommendations for screening in Turner syndrome diagnosis and throughout life

(Note: This table can be printed).

Get the latest news on genetic aortic and vascular conditions

If you have an interest in advancing the research, education, and treatment of genetic aortic and vascular conditions, sign up for emails from the GenTAC Alliance using the form to the right.

These communications are geared toward professionals and include information such as updates to best practices and treatment guidelines, upcoming scientific and clinical webinars, and newly developed tools for healthcare professionals and researchers.

Join the GenTAC Alliance Mailing List