What is Marfan Syndrome?

Marfan syndrome is a genetic condition that affects the body’s connective tissue. Connective tissue holds all the body’s cells, organs, and tissue together. It also helps the body grow and develop.

Connective tissue is made up of proteins. The genetic defect that causes Marfan syndrome is a mutation in a gene known as FBN1. This gene affects a protein called fibrillin-1. The abnormal fibrillin-1 protein leads to an increase in the activity of a growth factor, called transforming growth factor-beta (TGF-beta), and eventually leads to problems with connective tissue throughout the body. This, in turn, creates the features and medical problems associated with Marfan syndrome. Because connective tissue is found throughout the body, Marfan syndrome can affect many different parts of the body (see below):

- Aorta and other blood vessels

- Heart and heart valves

- Skeleton and joints

- Eyes

- Lungs

- Skin

- Tissue surrounding the spinal cord (dura which lines the dural sac)

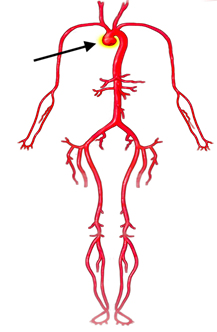

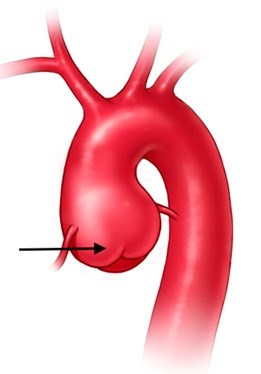

Some Marfan features can be more dangerous than others. One example is an increase in the size of the aorta, which is the main blood vessel that carries blood away from the heart to the rest of the body. When the aorta expands, it is called an aortic aneurysm. An aortic aneurysm may lead to a tear in the aorta (acute aortic dissection), which is life-threatening. Surgery to replace the enlarged aorta with an artificial graft can prevent aortic dissection. The eyes, mitral valve, skeleton, lungs, skin, nervous system, and the lining of the dural sac may also be affected. Marfan syndrome does not affect intelligence.

How common is Marfan syndrome?

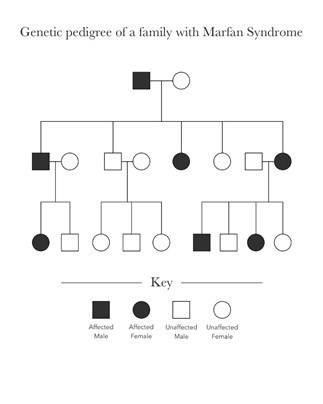

About 1 in 5,000 people have Marfan syndrome, including men and women of all races and ethnic groups. About 3 out of 4 people with Marfan syndrome inherit it, meaning they get the genetic mutation from a parent who has it. But some people with Marfan syndrome are the first in their family to have the condition. When this happens, it is called a spontaneous mutation. For someone with Marfan syndrome, each child they have has a 50% chance of also having this condition.

What are the features of Marfan syndrome?

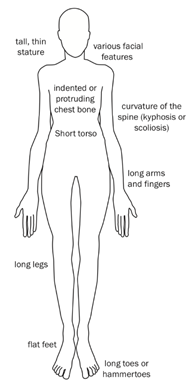

Every person’s experience with Marfan syndrome is slightly different. No one has every feature, and people have different combinations of the features. How serious each feature is can also vary. Importantly, many features change with age. Some features of Marfan syndrome are easier to see than others (Figure 1). These include:

- Long arms, legs, fingers, and toes (Figure 2, Figure 3)

- Tall for family; often tall and lanky (Figure 2)

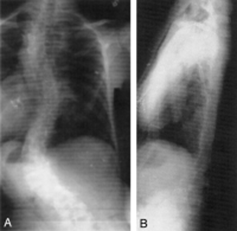

- Curved spine (scoliosis) (Figure 4)

- Chest wall sinks in (pectus excavatum) (Figure 5) or sticks out (pectus carinatum)

- Flexible joints including the knees, elbows, and fingers

- Flat feet

- Long, narrow face (Figure 6)

- Crowded teeth (Figure 7)

- Stretch marks on the skin that are not related to weight gain or loss

- Long arms, legs, fingers, and toes (Figure 2, Figure 3)

Other important features of Marfan syndrome involve the eye, heart and heart valves, lungs, and the connective tissue lining (dura) of the spinal cord. To correctly diagnose and evaluate for involvement of the eyes and heart, testing such as a slit-lamp eye examination and an echocardiogram are needed.

Features of Marfan syndrome may affect many organ systems:

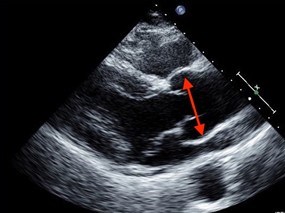

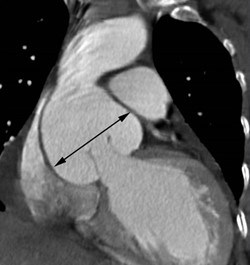

- Aorta and blood vessels: enlargement (or aneurysm) of the aorta as it exits the heart (aortic root dilation or aneurysm) (Figure 8 and Figure 9)

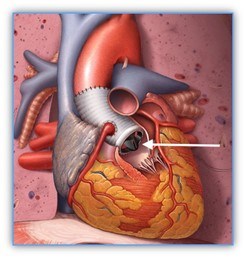

- Heart and heart valves: a floppy mitral valve which may cause regurgitation or “leaking” of the valve during the heartbeat (mitral valve prolapse which may lead to mitral valve regurgitation)

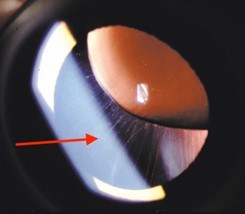

- Eyes: nearsightedness (myopia); dislocation of the lens (ectopia lentis) (Figure 10); a clouding of the lens at a young age (early-onset cataracts); a separation of the retina from the back of the eye (retinal detachment)

- Lungs: abnormal enlargement of the air spaces at the top of the lung, which may lead to a blister (blebs), or larger sacs (bullae). This may lead to a collapsed lung (pneumothorax)

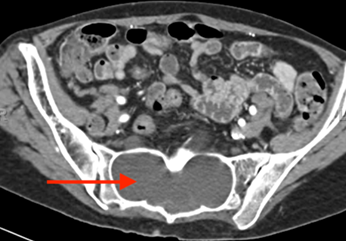

- Dural sac: abnormal connective tissue in the outer lining of the spinal cord may lead to a widening of the spinal canal in the lower spine (lumbosacral dural ectasia) (Figure 11)

What kind of testing is needed?

It is important to go to a doctor experienced with Marfan syndrome for a diagnosis. The doctor will examine many parts of the body as part of a complete physical exam. The doctor will also ask questions about medical and family history. This may include information about any family member who may have Marfan syndrome, an early heart-related or unexplained death, or a history of aortic aneurysm or dissection.

Individuals suspected of having Marfan syndrome should also have tests to identify Marfan features that cannot be seen during the physical exam, including:

- Echocardiogram: This is an ultrasound test to look at the heart, its valves, and the aorta (Figure 9).

- In adults, a CT scan or an MRI of the chest to look at the entire aorta is important after a diagnosis of Marfan syndrome.

- Electrocardiogram (EKG): This test checks heart rate and heartbeat.

- An eye examination, including a slit lamp evaluation to see if the lenses in the eyes are out of place (dislocated). It is important that a doctor looks inside the eye by fully dilating the pupils with eye drops.

- Other tests, such as a CT scan (computerized tomography) or MRI (magnetic resonance imaging) of the lower spine may be needed. It can help the doctor see if the sac around the spinal column is enlarged (dural ectasia), which is a spine problem that is very common in people with Marfan syndrome.

Genetic testing may also provide helpful information. If someone has a family history of Marfan syndrome, genetic testing can help show which family members have Marfan syndrome and need additional care. This is useful in young children who may not yet show signs of Marfan syndrome.

This example (Figure 12) demonstrates that an individual affected by Marfan syndrome (in black) may pass the gene for Marfan syndrome to his or her children. If someone in the family does not have Marfan syndrome (in white), that unaffected individual cannot pass on a trait for Marfan syndrome as he or she does not carry the mutated gene. (See Genetic testing for HTAD link).

Some of the outward features of Marfan syndrome can be found in other disorders related to Marfan syndrome, such as Loeys-Dietz syndrome or isolated thoracic aortic aneurysms. For this reason, genetic testing may be helpful when a diagnosis cannot be determined through an exam, family history, and imaging tests alone or when lens dislocation (ectopia lentis) is not present and features suggesting an alternative diagnosis are present. Knowing the precise diagnosis is critical to the follow up monitoring and treatment plan.

How is Marfan syndrome treated?

While Marfan syndrome cannot be cured, with diagnosis, monitoring and treatment, those affected can live a long, full life. Everyone with Marfan syndrome is different, depending on the severity of their features.

For some individuals with Marfan syndrome, some things need to be considered every day, such as medications and some limitations on physical activity and lifestyle. Then, there are routine doctor appointments, which may be yearly or more often, as well as other tests to make sure that signs and symptoms are not changing. Sometimes, when symptoms progress or the testing shows a change in the condition (such as significant enlargement of the aorta or leaking of the mitral valve), a doctor will recommend surgery. In most cases, individuals with Marfan syndrome will have time to plan for surgery; in some cases, immediate surgery may be needed.

People with Marfan syndrome are always at risk for growth or enlargement of the aorta. This growth mostly happens closest to the heart and just above the aortic valve, called the aortic root. The size of tje aorta is watched by an echocardiogram which is done at least once a year. Individuals with Marfan syndrome may need these tests more often if their aorta is large or getting to the point where doctors think they may need surgery. Some people need yearly CT or MRI scans (see testing section) to follow the aorta.

People with Marfan syndrome may be given medications to slow the rate of aortic growth. These medications include beta blockers (such as atenolol or metoprolol) to lessen the stress on the aortic wall or angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs such as losartan or irbesartan) which are believed to block the overactive growth factor (TGF-β) in Marfan syndrome. The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) also recently warned that people with Marfan syndrome and other aortic aneurysm conditions should avoid commonly used antibiotics called fluoroquinolones (includes Avelox, Cipro, Factive, Levaquin, and Ofloxacin). The reason for this recommendation is that recent medical studies have shown that people who have taken a fluoroquinolone are twice as likely to have an aortic aneurysm or dissection than those who have not taken one of these drugs.

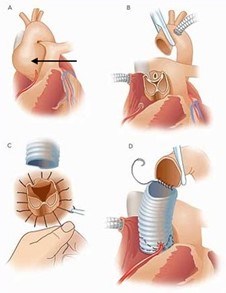

Once the aorta reaches 5 cm, aortic root replacement surgery is recommended (Figure 13). This is open heart surgery. Heart surgeons will replace the aortic root with a graft. In this surgery, an individual’s own aortic valve may be sewn inside the graft (a valve sparing root replacement) (Figure 14), or they may receive an artificial valve along with the graft (a Bentall procedure) (Figure 15). If a person is given a new valve, it will likely be a mechanical valve. A mechanical valve requires treatment with a blood thinner (anticoagulant) called warfarin. In some cases, aortic root replacement surgery is performed when the aortic size is less than 5 cm, like if someone has a family history of aortic dissection (when the wall of the aorta tears) or if the aorta is growing very rapidly.

People with this condition may experience leaking (regurgitation) of the mitral valve. In Marfan syndrome, it is common for one or both of the mitral valve leaflets to move backwards into the upper chamber of the heart when the heart beats (mitral valve prolapse). This problem may also require heart surgery to correct.

Are there limitations on exercise?

In general, most people living with Marfan syndrome can and should exercise regularly through low-intensity (aerobic), low-impact activities adapted to meet their specific needs (Figure 16).

Nearly every activity can be done at different intensity levels, and no recommendation applies to every case. For example, shooting baskets in the driveway is different from playing a full-court basketball game. Biking ten miles in one hour on a level course is different from doing a triathlon.

Individuals with Marfan syndrome need to discuss physical activities and activity levels with their physician so they can safely exercise, especially as they age.

- Competitive and contact sports increase the risk of injury. Doctors worry about:

- Increased heart rate and blood pressure can put added stress on the aorta

- Head impact can damage the eyes and may lead to worsening lens dislocation or a retinal detachment

- Stress on the bones and joints can lead to added pain and joint dislocations

- Bruising and internal bleeding due to certain medications (such as blood thinners)

- There are several things to consider when deciding if a sport or activity is safe:

- Favor non-competitive activity

- Perform activities at a non-strenuous pace

- Choose an enjoyable activity that can be performed 4–5 times per week for 30 minutes at a time

- Stay at an aerobic level of work (not breathing hard, could easily carry on a conversation during the activity)

- Wear protective gear as appropriate

- Consider traditional yoga for relaxation and stress reduction

- Individuals should not test their limits

- When choosing an activity, the three C’s: competition, collision, and contact, should be avoided. Exercises to avoid include:

- Intense isometric exercises (where specific muscles are contracted without moving, such as weightlifting, pullups, pushups, planking or wall sits, or those leading to muscle fatigue or straining).

- Contact sports that may involve a blow to the head; this will help avoid eye injuries

- Exercise to the point of exhaustion (breathless, unable to speak)

How does Marfan syndrome affect one’s ability to start a family?

Pregnancy increases stress on the heart and blood vessels. This can be especially dangerous in women with Marfan syndrome. While there is no clear way to know if someone can have a low-risk pregnancy, several points should be considered:

- Pregnancy risks should be discussed with doctors before considering pregnancy

- Even if the aorta is not significantly enlarged, an individual should be monitored closely during pregnancy and early after delivery

- The risk of serious aortic events such as tear (aortic dissection) is higher if the aorta is bigger than 4.0 cm.

- Individuals with Marfan syndrome should know the symptoms of acute aortic dissection; during pregnancy, aortic dissection may occur even when the aorta is not enlarged, and can occur several days after delivery

If someone with Marfan syndrome has an artificial aortic valve, they should talk to their doctor about the risks of warfarin on the developing fetus. If they have had aortic root surgery, their risks during pregnancy may be lower. However, this does not remove all risk since other parts of the aorta can enlarge and tear (dissect) related to pregnancy.

If someone does get pregnant, it will be considered high-risk (a term doctors use). They should be monitored by a cardiologist and a maternal-fetal medicine specialist or high-risk obstetrician during the pregnancy. During pregnancy, the aorta should be evaluated by echocardiography at least every three months. Before getting pregnant, ythe entire aorta should be scanned with CT/MRI. These tests will give doctors a better picture of the whole aorta.

Delivery should be by the least stressful method possible. We do not yet know whether a controlled vaginal delivery or a Cesarean section (C-section) is less stressful for people with Marfan syndrome. A pregnant person should talk with their doctors should talk about the best delivery method . It is important to work with doctors who are familiar with Marfan syndrome. C-section is not absolutely necessary because of Marfan syndrome, but may be indicated for any of the usual reasons that would apply to any pregnancy. If possible, individuals with Marfan syndrome may want to try to have children earlier in life and when the aorta is not enlarged.

Certain medications cannot be used during pregnancy as they increase the risk of birth defects and fetal loss. These include:

- Angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors (such as enalapril or captopril)

- Angiotensin receptor blockers (such as losartan)

The beta blocker metoprolol is low-risk during pregnancy. Atenolol is not recommended during pregnancy. Lower spine (lumbosacral) disease and enlargement of the sac around the spine (dural ectasia) may affect the use of an epidural. Pre-delivery discussion with one’s doctors is recommended.

In addition to careful assessment of the risk for women contemplating pregnancies, couples in whom the underlying genetic defect is known may consider prenatal or pre-implantation diagnostics.

- Prenatal testing

- Prenatal testing is the technique in which early in the pregnancy (11-12weeks) the presence of the genetic defect is checked by means of a so-called villous sampling in which a piece of placenta (which is of fetal origin) is punctured away. If the result is abnormal, the pregnancy will be interrupted. With this technique, pregnancy occurs naturally but there is a 50% chance that the pregnancy must be interrupted.

- Pre-gestational diagnostic

- PGD is an in vitro fertilization technique that allows for testing of the early embryo for the specific genetic mutation that causes Marfan syndrome. Only embryos without the genetic mutation are implanted. With this technique, pregnancy is artificially established with an embryo that does not carry the abnormal FBN1 gene.

In both cases, it is necessary to know the specific mutation in the gene leading to Marfan syndrome as well as having dedicated pre-conception counseling.

What are the signs and symptoms of an acute aortic dissection?

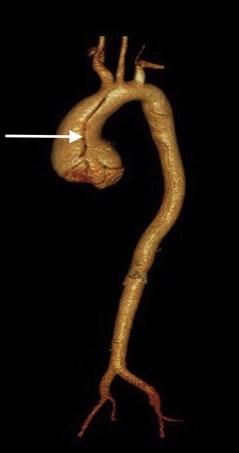

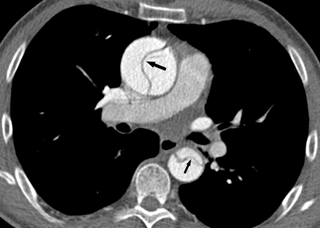

Aortic dissection (a tear in the wall of the aorta) is very dangerous and must be treated as soon as possible (Figure 17, Figure 18).

We think there are probably 5,000-10,000 dissections a year in the United States. However, it is likely that many dissections are reported as a “heart attack” or “sudden death,” when the cause is actually a dissection.

An individual with Marfan syndrome is at much greater risk for an aortic dissection than the general population. It is important to know the signs of an aortic dissection and what to do.

Signs and symptoms of acute aortic dissection may include:

- Sudden onset, severe or sharp chest, back, neck/head, or abdominal pain

- Pain described as “ripping” or “tearing”

- Pain radiating (traveling) from the chest to the back, head and neck, abdomen, or legs

- Chest pain associated with fainting (syncope)

- Acute shortness of breath

- Acute stroke symptoms or inability to use an arm or leg

- Chest pain and a newly leaking aortic valve

- Unexplained pain and the feeling that “something is very wrong” or a “sense of doom”

Chest pain can have many causes, but when a person has Marfan syndrome, it is very important to check for aortic dissection. If they have symptoms that could be due to an aortic dissection, they should call 911 and get to an emergency room right away. Knowing that someone has Marfan syndrome help if they have unexplained chest, back, or abdominal pain.

Since emergency rooms may be very busy and personnel may not know a lot about Marfan syndrome, individuals with the condition should plan to advocate for themselves if they have these symptoms and end up in an ER. The doctors and nurses at the hospital should be told what an individual knows about their condition. People with Marfan syndrome should tell their doctors, nurses, and emergency personnel that they have Marfan syndrome and are concerned about the symptoms related to an aortic dissection, so they can be more quickly evaluated for the condition.

A medical alert bracelet can alert emergency personnel right away that someone with Marfan syndrome is at risk for a life-threatening dissection.

(from Setty R, et al. Int J Surg Case Reports: 2018; 63: 113-117.)

Where can I learn more about Marfan syndrome?

The Marfan Foundation: www.marfan.org

Get the latest news on genetic aortic and vascular conditions

If you have an interest in advancing the research, education, and treatment of genetic aortic and vascular conditions, sign up for emails from the GenTAC Alliance using the form to the right.

These communications are geared toward professionals and include information such as updates to best practices and treatment guidelines, upcoming scientific and clinical webinars, and newly developed tools for healthcare professionals and researchers.

Join the GenTAC Alliance Mailing List