What is Nonsyndromic HTAD?

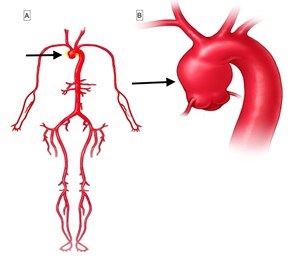

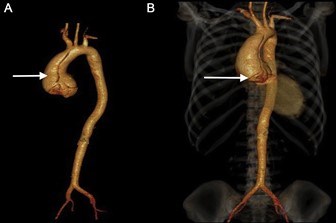

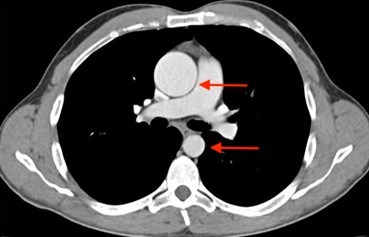

The aorta is the main blood vessel that carries blood away from the heart to the rest of the body (Figure 1). An aortic aneurysm is an enlargement of the aorta. When the aortic aneurysm is present in the chest it is known as a thoracic aortic aneurysm (Figure 2). Aortic aneurysms typically grow very slowly and do not cause symptoms unless a complication from the aneurysm occurs. When a thoracic aortic aneurysm reaches an unsafe size, an aortic dissection can occur (Figure 3). Aortic dissection is a tear in the inner lining of the wall of the aorta that can result in decreased blood flow to the body or an aortic rupture. Aortic dissection is a very serious complication of an aneurysm and can be fatal.

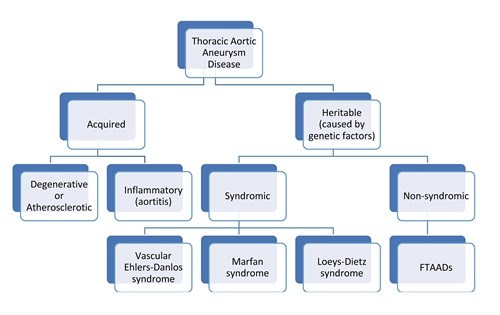

There are many causes for thoracic aortic aneurysms (Figure 4).

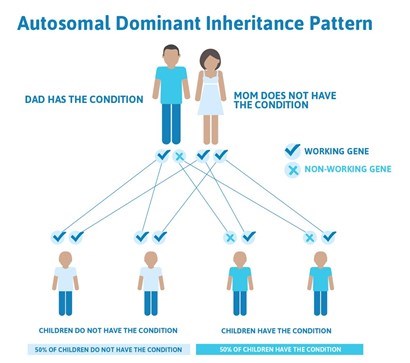

When thoracic aortic aneurysms are caused by hardening of the arteries (degenerative or atherosclerotic aneurysms), inflammatory or infectious conditions (called aortitis), they are called acquired aneurysms. However, aortic aneurysms in the chest can also be caused by genetic mutations, which are uncommon differences or changes in someone’s genetic code. Nonsyndromic HTAD follows an autosomal dominant inheritance pattern. This means that when a parent has the condition, there is a 50% chance of passing on the same trait to each child (Figure 5). In nonsyndromic HTAD, there can be a variable age of onset for thoracic aortic aneurysms in a family.

When thoracic aortic aneurysms are inherited from a parent who has a genetic mutation, they may occur as part of a syndrome. A syndrome is where several physical changes occur in a recognizable pattern. Marfan syndrome and Loeys-Dietz syndrome are two examples of syndromes that have thoracic aortic aneurysm as an important feature.

When multiple family members have thoracic aortic aneurysms (i.e., familial pattern), but don’t have the physical features of a syndrome, it is clinically classified as nonsyndromic heritable thoracic aortic disease (nsHTAD). Some people also call this Familial Thoracic Aortic Aneurysm and Dissection (FTAAD) to highlight the risk of aortic dissection.

When people with nsHTAD have genetic testing, a mutation (pathogenic variant), or harmful change in a gene, may be found. However, a mutation is not always identified in these families—even when there is a clear pattern of inheritance in the family. This is most likely because the genetic testing that is done today is not able to identify every possible genetic change leading to aneurysm disease. New mutations that explain nsHTAD continue to be discovered by researchers.

How common is nsHTAD?

Nonsyndromic HTAD is estimated to be the cause of at least 1 out of every 5 thoracic aortic aneurysms and dissections. It is difficult to know how often this condition occurs in the population because aneurysms usually don’t cause any noticeable symptoms until dissection occurs and because the familial pattern may not be recognized. Almost 30,000 deaths in the United States are caused by aortic disease (including ruptures and dissections) each year, and it is not known how many of these are nsHTAD cases

What are the features of nsHTAD?

In evaluating the individual for suspected nsHTAD, it is important to compile a careful family history. One should ask about any aneurysm disease (cerebral, thoracic, and abdominal) or unexplained sudden death occurring in parents, siblings, and children as well as in more distant relatives (such as aunts, uncles, grandparents, etc.). As described above, nsHTAD usually occurs without a consistent pattern of additional physical changes which are recognizable on a physical examination. However, people with nsHTAD may have mild features that are often found in other connective tissue conditions. These features may include, but are not limited to, flexible joints and mild curvature of the spine (scoliosis). Some people with specific types of nsHTAD, such as that due to ACTA2 mutations, may have a finding on the skin called livedo reticularis (a lacy pattern of the veins on the skin) or a special eye condition called iris flocculi (which requires a slit lamp eye exam for recognition). Since many people do not have obvious features, the diagnosis is not often discovered early in life. nsHTAD is often diagnosed after an aortic dissection occurs, when a thoracic aortic aneurysm is discovered during imaging (such as an echocardiogram, CT, or MRI) performed for other reasons, or when family members of a relative with an aortic dissection or aneurysm are being screened.

Some of the genes that cause nsHTAD have been identified and, in some cases, there may be patterns on examination of the individual or on vascular imaging that are clues to a specific gene mutation. Researchers are working on new ways to determine features that are relevant to the different genes causing nsHTAD.

What kind of testing is needed?

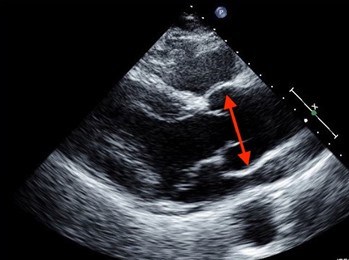

Nonsyndromic HTAD is suspected when there is a pattern of thoracic aortic aneurysm in a family. nsHTAD is also often suspected when a person in the family has a thoracic aortic aneurysm or aortic dissection, especially when young, and there isn’t evidence for a syndrome or other obvious cause. If someone suspects they have nsHTAD, it is important for them to see a doctor for evaluation. Cardiovascular imaging (such as an echocardiogram (Figure 6), CT scan (Figure 7) or MRI) and genetic testing (as appropriate) are important tools in the evaluation. Echocardiograms or CT scans are performed on the first-degree relatives (parents, siblings, and children) of the person with a thoracic aortic aneurysm to determine if there is any aortic enlargement. Genetic testing may be performed, but it is important to have genetic counseling to fully understand the results. Individuals will be informed about the possibilities, consequences, and drawbacks of genetic testing prior to the study, and they should also receive appropriate information on the interpretation of the genetic test result afterwards.

Even if genetic testing is negative, meaning no changes were found in the genes associated with nsHTAD, a person may still have the disease. Researchers are still trying to identify more genes that cause nsHTAD. Therefore, even if an individual is not found to have a gene mutation known to cause their thoracic aortic aneurysm, their first-degree relatives should have imaging tests to determine if anyone else in the family also has a thoracic aortic aneurysm. When nsHTAD clearly runs in a family, but no gene mutation is found, relatives of the affected person must have periodic screening for aneurysms throughout their lives, too.

Besides imaging the thoracic aorta, people with nsHTAD should undergo periodic screening of other arteries, including those in the brain, abdomen, and pelvis. This is because gene mutations causing nsHTAD may occasionally lead to aneurysms in other blood vessels.

How is nsHTAD treated?

Treatment for nsHTAD will be based upon the latest information available. It will consist of important strategies:

- Medical therapy to potentially reduce the rate of aortic enlargement. This may include a beta blocker (such as atenolol or metoprolol) and/or an angiotensin receptor blocker (such as losartan or irbesartan). If the blood pressure is elevated, reducing the blood pressure to normal is important.

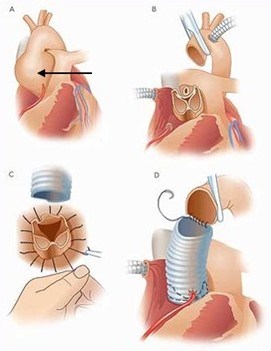

- Preventive aortic surgery to replace aortic aneurysm with a synthetic vascular graft sewn into place.

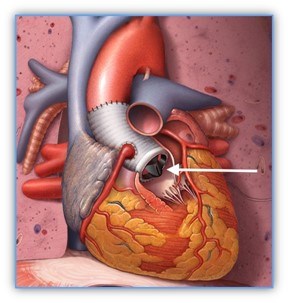

The decision to perform surgery is based upon symptoms, the specific genetic mutation causing the nsHTAD, the rate of aortic growth, family history, and, most importantly, the diameter of the aorta. Once the aorta reaches a critical size, aortic root and/or ascending aortic replacement surgery is recommended. This is open heart surgery. A heart surgeon will replace the aortic root and/or the ascending aorta with a synthetic graft. In this surgery, an individual’s own aortic valve may be sewn inside the graft (known as a valve sparing root replacement) (Figure 8), or they may receive an artificial heart valve along with the graft (known as a composite valve graft or Bentall procedure) (Figure 9). If they are given a new valve, it will likely be a mechanical valve. A mechanical heart valve requires treatment with a blood thinner (anticoagulant) called warfarin.

Are there limitations on exercise?

Currently, physical activity guidelines are based on research that has been done on syndromic and acquired thoracic aortic aneurysms. We do not have data to recommend specific activity guidelines for people who have a mutation in each of the specific genes known to cause nsHTAD.

Individuals should discuss physical activities and activity levels with their physician so they can safely exercise, especially as they age.

However, general guidelines for physical activity include the recommendations for low to moderate levels of aerobic exercise depending upon specific circumstances. It is recommended to avoid competitive and contact sports and to recognize that the increased blood pressure can put added stress on the aorta.

- There are several things to consider when deciding if a sport or activity is safe:

- Favor non-competitive activity.

- Perform activities at a non-strenuous pace.

- Choose an enjoyable activity that can be performed 4–5 times per week for 30 minutes at a time.

- Stay at an aerobic level of work (not breathing hard, could easily carry on a conversation during the activity).

- Consider traditional yoga for relaxation and stress reduction.

- Do not test limits.

- When choosing an activity, avoid the three C’s: competition, collision, and contact. Exercises to avoid include:

- Intense isometric exercises (contracting specific muscles without moving, such as weightlifting, pull-ups, push-ups, planking or wall sits, or those leading to muscle fatigue or straining).

- Exercise to the point of exhaustion (breathless, unable to speak).

How does nsHTAD affect one’s ability to start a family?

Currently, pregnancy guidelines are based on research that has been done on syndromic and acquired thoracic aortic aneurysms. We do not have data to recommend specific pregnancy guidelines for people who have a mutation in each of the specific genes known to cause Nonsyndromic HTAD. However, when the aorta is dilated, a person with Nonsyndromic HTAD will be at even higher risk of aortic complications during pregnancy. Individuals with Nonsyndromic HTAD should discuss with their cardiologist and geneticist before becoming pregnant. Pregnancy in people with Nonsyndromic HTAD is considered high-risk, and these individuals should have an evaluation by a maternal-fetal medicine specialist or high-risk obstetrician and cardiologist during pregnancy. If pregnancy occurs, a beta blocker such as metoprolol may be used to lessen the stress on the aorta during pregnancy. Echocardiograms are recommended during pregnancy and methods to lessen the blood pressure during labor and delivery, such as epidural anesthesia, avoiding pushing, and consideration for a cesarean section delivery (depending upon the circumstances), may be recommended.

In addition to careful assessment of the risk for women contemplating pregnancies, couples in whom the underlying genetic defect is known may consider prenatal or pre-implantation diagnostics.

- Prenatal testing

- Prenatal testing is a technique used in the context of a naturally occurring pregnancy. Early in the pregnancy (11-12 weeks) the presence of the genetic defect is checked by means of a so-called villous sampling. In this process, the placenta (which is of fetal origin) is punctured and a piece is taken as a sample. Because the sampling poses a small risk of miscarriage, this testing is not recommended unless the family plans to terminate the pregnancy in the event of an abnormal result.

- Pre-gestational diagnostic (PGD)

- PGD is a technique that was developed more recently. It requires the use of artificial insemination technology. Embryos are developed via an in vitro fertilization procedure. For this, oocytes are removed from the ovaries and are fertilized with sperm in a test tube. In an early stage of embryo development, one cell is subsequently removed for testing for the presence of the genetic defect. Only non-affected embryos are placed in the uterus.

What are the signs of an acute aortic event? What should be done if one occurs?

Aortic dissection (a tear in the wall of the aorta) (Figure 3) is very dangerous and must be treated as soon as possible.

We think there are probably 5,000-10,000 dissections a year in the United States. However, it is likely that many dissections are reported as a “heart attack” or “sudden death,” when the cause is actually a dissection.

It is important to know the signs of an aortic dissection and what to do.

Signs and symptoms of acute aortic dissection may include:

- Sudden onset, severe or sharp chest, back, neck/head, or abdominal pain

- Pain described as “ripping” or “tearing”

- Pain radiating (traveling) from the chest to the back, head and neck, abdomen, or legs

- Chest pain associated with fainting (syncope)

- Acute shortness of breath

- Acute stroke symptoms or inability to use an arm or leg

- Unexplained pain and the feeling that “something is very wrong” or a “sense of doom”

A medical alert bracelet can raise alert emergency personnel right away for those at risk for a life-threatening dissection.

Where can I learn more about nsHTAD?

Genetics Home Reference: https://ghr.nlm.nih.gov/condition/familial-thoracic-aortic-aneurysm-and-dissection#sourcesforpage

Gene Reviews: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK1120/

The Marfan Foundation: https://www.marfan.org/familial-aortic-aneurysm

Get the latest news on genetic aortic and vascular conditions

If you have an interest in advancing the research, education, and treatment of genetic aortic and vascular conditions, sign up for emails from the GenTAC Alliance using the form to the right.

These communications are geared toward professionals and include information such as updates to best practices and treatment guidelines, upcoming scientific and clinical webinars, and newly developed tools for healthcare professionals and researchers.

Join the GenTAC Alliance Mailing List